I've been spending a lot of time recently up in the loft of our office where we have a somewhat messy and chaotic work table where we make models.

I often find myself spending entirely too much time making physical models of the designs I am working on. Not that this is time wasted, but in the professional world, you can not possibly charge enough or financially justify the making of physical models unless you employ shamelessly low-paid interns to do the work. And that would mistake the product for the process.

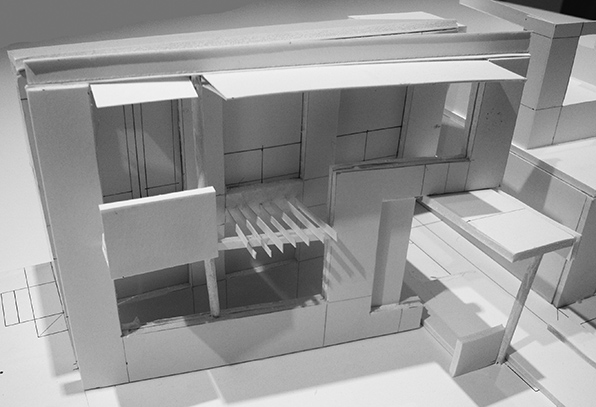

Real models (as distinguished from computer models) are very popular. Prospective clients love looking at them and they have enough of an abstract quality to resist too much projection into them. They are relatively small and kind of cute. These kinds of models, crafted from basswood and finely honed, are usually just show models, not the working design tools of architects. Working models, of torn paper and glue blobs, are generally not dragged out for the public’s viewing, resplendent as they are with the obvious signs of misstakes and decisions taken and abandoned.

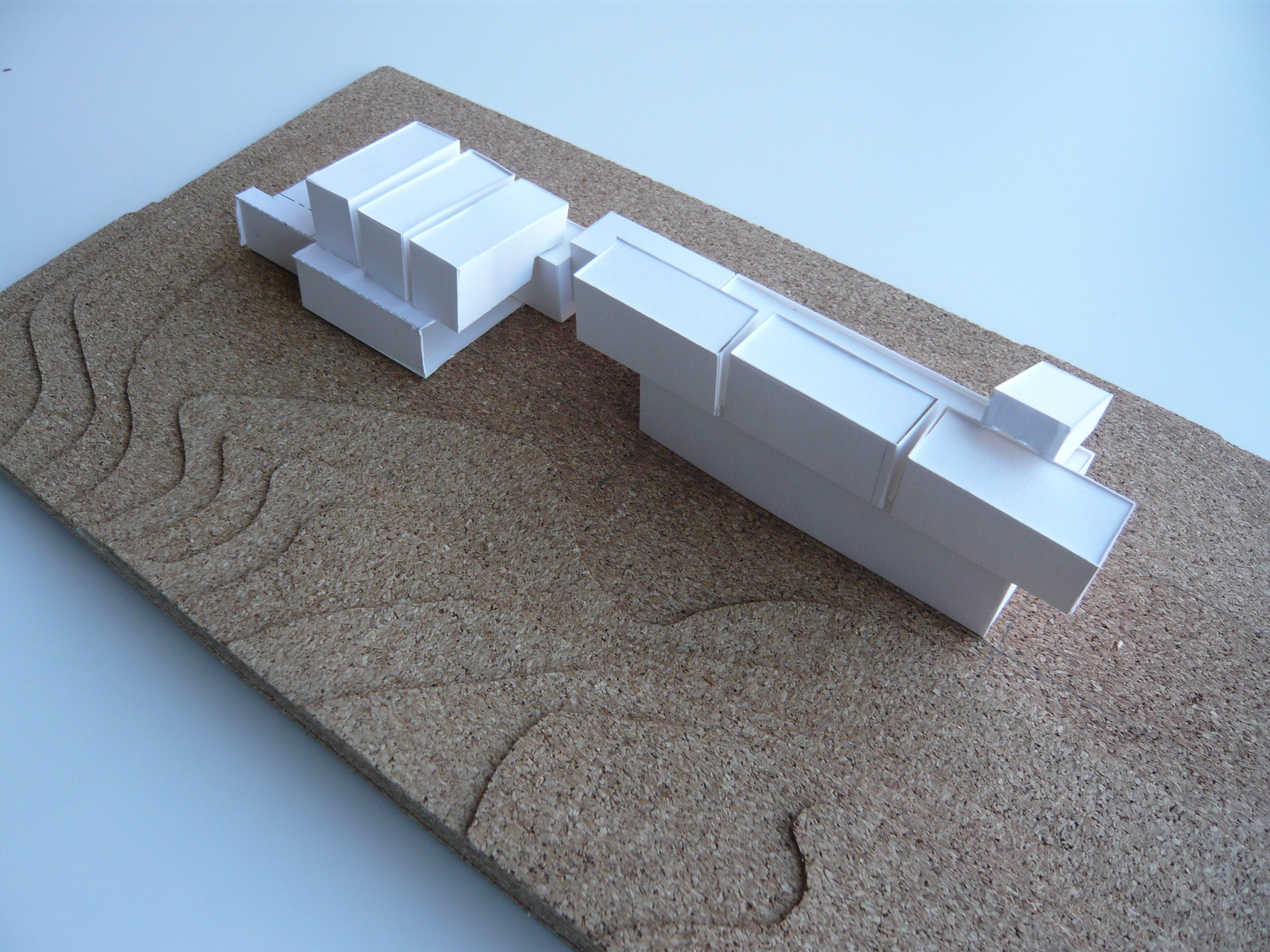

But it is those same process models that so many architects love, that are an integral part of learning in architecture school, and that so often get jettisoned from the design process in the professional world. Some offices still employ model-makers or interns that act as such, but this is usually only for the pretty presentation models described above. The reality is that most architects as they get older, no longer mess around with scissors and paper, glue and xacto knives. It takes a really long time to make all the contours that make up the site for a model on a hilly site. It takes a really long time to cut and paste, recut and re-glue, tear apart and stick back together, all the pieces and parts of a model that, in the end, has meaning for the designer and maker, but its very messiness and palimpset quality, makes it difficult to present to anyone else.

And yet, it is all the dumb time spent cutting contours, glueing and waiting to dry, that makes physical models worth the effort. For while all this semi-mindless work is taking place, you are literally spending time with the project, with the nascent design sitting in front of you. You can not quickly come up with acceptable solutions or fantastically dynamic computer models that you can toggle on and off the sunlight at the proper latittude, longitude and time of year. Rather you have to sit there, holding two pieces of cardboard together while the glue sets long enough to cut yet another chunk of foam board or such. You have time to think, to ponder, forced upon you by the slowness of the making.

The working design model can help to generate great solutions, spatial constructions that drawings and computer models can not quite get at. But more importantly, making physical models generates time, creates enough engagement with the process to shut out emails and phone calls, but does not give up its ends so easily or quickly. Making models creates time, more precious than any other tool wielded, any software employed, any solution quickly grasped.