"It was beautiful in Longmont. Under a tremendous old tree was a bed of green lawn-grass belonging to a gas station. I asked the the attendant if I could sleep there, and he said sure; so I stretched out a wool shirt, laid my face flat on it, with an elbow out, and with one eye cocked at the snowy Rockies in the hot sun for just a moment. I fell asleep for two delicious hours, the only discomfort being an occasional Colorado ant. And here I am in Colorado! I kept thinking gleefully. Damn! damn! damn! I'm making it! And after a refreshing sleep filled with cobwebby dreams of my past life in the East I got up, washed in the station men's room, and strode off, fit and slick as a fiddle, and got me a rich thick milkshake at the roadhouse to put some freeze in my hot, tormented stomach."Jack Kerouac, On The Road

The gas station with the lawn was Johnson's Corner. This is not the same cinnamon-roll-laden Johnson's Corner truck stop on I-25 outside of Loveland, but the cast concrete art deco inspired filling station that faced demolition in 2002. As it was threatened because of road expansion, the building was moved to its current location on the edge of the new urbanist community of Prospect just south of Longmont.

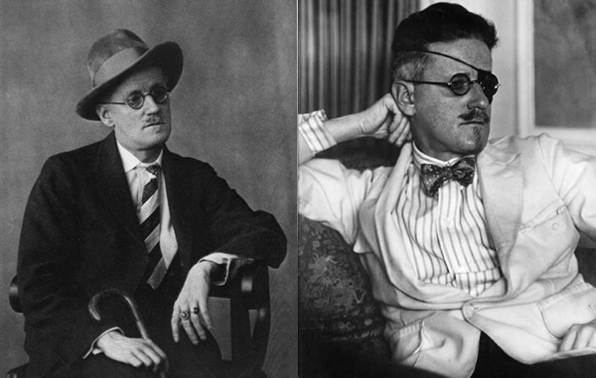

As you can see, though not demolished, the building was preserved but not renovated and it is slowly falling apart inside its protective fence. The plans are to create a small cafe and hopefully, a small patch of lawn-grass.

Moving a building to save it is a dubious proposition at best and especially so if the move requires as much demolition as this one did. Generally, removing a structure from its context also means that it is no longer eligible for National Register status as well as some much-needed federal grants for renovation. I hope that funds are found soon and this building can find a new use and it does not suffer the same fate as the Boulder Depot which has moved twice and is still waiting for some new use to bring it back to useful life.