Yale Art and Architecture Building

I recently made a trip back to New Haven and visited my grad school haunt, the Yale Art and Architecture building. To say that it is a remarkable building does not do justice to its monumental and cruel presence. Siting on the edge of Yale's collegiate gothic campus, the stark Brutalist hulk has a severe monumentality that perfectly reflects the role of architecture and architects at its 1963 completion.

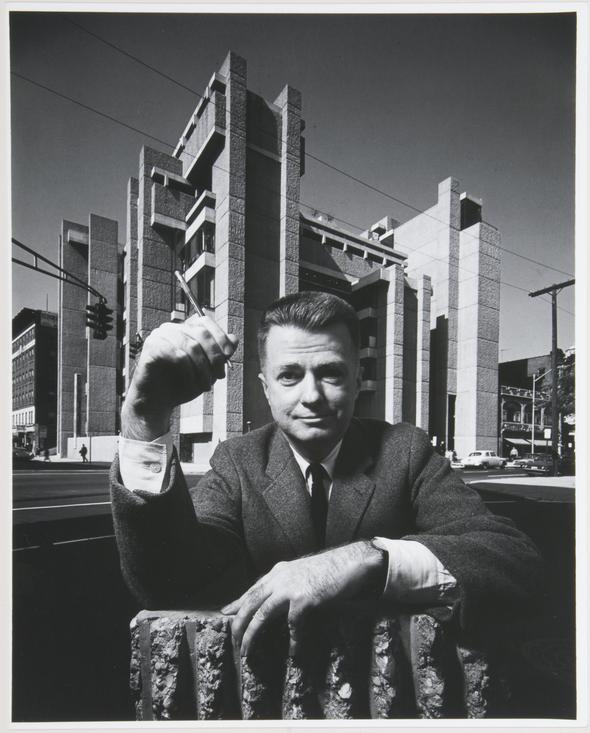

Designed by then dean Paul Rudolph and completed in 1963, the Yale Art and Architecture building was one of a number of structures completed on Yale's campus that year that marked a definitive break from the university's architectural past. The Art and Architecture building is primarily concrete - massive vertical corrugated walls and smoother, board-formed horizontal spans. There are other building materials - some glass and steel - but the structure was conceived and executed as a single, sculptural concrete mass. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the vertical corrugations make the walls seem heavier and more massive, exposing the tough aggregates and creating ragged linear shadows.

The building consists of art and architecture studio spaces, faculty offices and seminar rooms, a subterranean lecture hall, and vast library and art gallery spaces. Centered on the studio floors are the Pits, large, open rooms which are the locations of the architectural review juries which are so critical to the education of young architects.

Rudlolph's building is really a like a little city unto itself. The spaces flow into each other and are interlocked in complex and surprising ways. It is a bit of fortress and established and reinforces the insular, tribal aspects of the architects and architecture culture. It is a place that turns its back on the city and the university and proposes itself as a vision of a bold, new future, a stark rejection of the pseudo gothic architecture of Yale's past and by extension the Old World that had only recently emerged from a world war. It is heroic and naturally, it is also tragically flawed in its myopic quest to erase the past.

Given all of that, I must admit I love this building. That may be as much nostalgia on my part as it is rational architectural appreciation. Rudolph's building is a remarkable reflection of its time and use and it is an undeniably bold artistic invention.

The building looks much more like its original self now than it did when I attended. In 1969, amidst the student uprisings across most of the US, the building was set on fire, possibly by a disgruntled student. A subsequent renovation and repair installed partitions and partial floors which cut off the interconnected spaces from each other. In the past decade or so, the building has undergone a renovation by Beyer, Blindell, Belle and most recently an addition by alumn Gwarthmey Seigel. The spaces now flow seamless into each other and while the overall building has been spruced up, it still retains is tough, uncompromising nature.

The labyrinthine stairs are still there with their vertiginous spaces and odd alcoves. And the concrete walls bear even more marks of the thousands of architecture students wearily treading up and down, innumerable cups of coffee spilled and mixed into the patina of the aging concrete. Much of the building looks like a relic, but it likely did the day it was completed.

Strangely, the building did not have the emotional resonance for me that I thought it might. Possibly too much time has passed for me, possibly the alterations have changed the place too much. Possibly the building does not invite itself to be housed in the emotional memory of its inhabitants the way other structures do. It is too tough and proud for mortals.