on the dominant role of functionalism and an alternative approach to design that neither favors formalism nor eschews function

I. M. Pei's NCAR building, Boulder, Colorado, part 2

Boulder 2014 Structures of Merit - some of the best of the 1960's

As Chair of Boulder's Landmarks Board, I have been heading up an effort to engender greater appreciation and recognition of some of Boulder's remarkable 1960's architecture.

Boulder really flowered in this decade as a number of new, high tech industries moved to town and the overall prosperity lead to a explosive building boom. On the scene were a number of talented architects that, along with their clients, embraced the future and created buildings that were unconventional and intriguingly creative.

The City of Boulder had as a part of the Preservation Program an arm called the Structures of Merit. Many years ago this was a kind of preservation-lite that entailed some limited protection from demolition of designated buildings. The program's restriction were removed and the Structures of Merit designation became purely honorary, with no limitations on potential building changes or demolitions. As the teeth were taken out of the program it was largely abandoned.

Last year in an effort to raise awareness of architecture of the recent past, the Landmarks Board decided to revive the Structures of Merit program as a kind of architectural awards. The buildings shown here are the first crop of this renaissance of the Structures of Merit Program.

These buildings will be designated this year with the support of their current owners and I hope this is the first step in extended the range of the Landmarks Board from a Bureacracy-of-No to one of more inclusion, greater outreach and better community partnership.

From top to bottom:

Boulder Eye Clinic, by Charles Haertling

Thron House, by Hobart Wagner

Kahn House, by Charles Haertling

Brenton House, by Charles Haertling

Sirotkin House, by Tician Papachristou

Willard House, by Charles Haertling

Price Tower

In northeast Oklahoma, just west of the Osage Indian Reservation, lies Bartlesville, home of Phillips Petroleum and Frank Lloyd Wright's only completed "skyscraper" building, the Price Tower.

The history of the Price Tower is long and complex and Frank Lloyd Wright's recycling of an earlier unbuilt tower design is well documented. It is all worth reading and a little study, but it really does not prepare you for a confrontation with the building itself. And even though by today's standard the building is not so tall and the motifs a bit dated, the building itself has a magnificent sculptural presence.

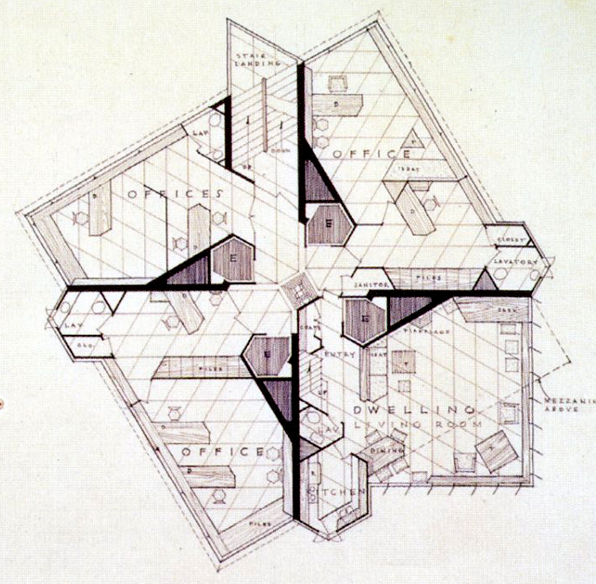

Designed for multi-purpose usage, the tower houses offices and residential space on each of its central floors. From the outside of the building, the horizontal slats and fenestration define the office spaces while the vertical louvers identify the residential portions. Instead of subdividing the building vertically and stacking one use exclusively upon the other, Wright and his client choose to intermingle the two, with only the base and top-most floors housing a single function.

It is often easy to forget how ornate Wright's work was when fully executed. The prairie houses he created had such a streamlined, simple and bold expression, that only actually visiting a work reveals the little carved panels and decorative embellishments. At the Price Tower, those embellishments take center stage as patterned, aged copper panels dominate the entire building and find smaller, more refined expressions on the interior.

Like so many of Wright's best works, the Price Tower is simultaneously bold and sculptural, refined and almost precious. It tetters on the edge of gilding the lily with its decorative motifs splashed across so much of the lower levels. But it is worth remembering the unlike so many of his modernist European contemporaries like Gropius and Mies, Wright believed in a very earthy kind of romantic sensibility and trancendent Beauty. In that sense, the Price Tower, like Wright himself, is a last echo of the nineteenth century passing through the end of the millenium. The Price Tower feels like a beautiful mash-up of Craftsman materiality and the Jetsons sci-fi retro-futurism.

It's not exactly on the beaten path, but a visit to the building is worthy of a prolonged side trip. You can have a drink in the roof top bar or even stay in the boutique hotel created within, the Price Company's offices having long since removed themselves. And in Bartlesville you can get quite excellent chicken-fried steak, so go to it.

(Much of the historical info and imagery here is from The Price Tower, published by Rizzoli, Anthony Alofsin, Editor)

programmatic determinism

why are so many modern houses such bad neighbors?

In the last few days, I have received, along with the usual breathless announcements from the architectural press, images of a number of new, modern houses that share a disturbing characteristic. What so many of these houses have in common is their disdain or outright contempt for their more mundane neighbors.

I am a strong believer that contemporary buildings should reflect contemporary times. That doesn't always mean that I design "modernist" buildings, but certainly the language of modernism - spatial as much as material - is always at play in my work. I am also almost daily fending off criticisms of modernism by non-architects. There are a number of reasons I think that most folks dislike modernist designs, some of them a bit knee-jerk, many of them based on only having experience with bad modernist designs, but some of them very well deserved.

Why are so many modern houses such bad neighbors? Modernism owes much of its appeal to its boldness and often stark articulation. When placed is what is otherwise a fairly traditional neighborhood, this is often strikingly harsh and confrontational. Let me try to outline why I think this has come to pass:

1. First, modernism is born in the crucible of individual liberty and an outright denial and contempt for previous historical forms. A modernist building is a work of art and is often likewise as non-contextual. It doesn't matter who or what your neighboring buildings might look like, the architect is genius and the work is a masterpiece and owes no debt to its philistine neighbors.

2. Second, traditional houses were proud manifestations of the homeowners wealth and status and most importantly, their public role as citizens. Windows were not only to let in light and air, they were also a part of the forthright facade of the building, looking out at their fellow neighbors and asserting a public role. Modernism's championing of functionalism over formalism has in a sense reduced the window into a technological device for the passage of sunlight and possibly the movement of air. Windows are placed based on views and light and privacy, not as the public face of the private life of the homeowners. This is symptomatic of,

3. Traditional houses were public buildings of a sort. Even though the private lives of the residents might roil within, the house was the public face of that family and projected their status, taste and prejudices out to the neighborhood and the city beyond. By contrast, most homes over the last 50 years or so, are not built to project out in to the world, but rather to be a retreat from it. Homeowners consistently respond that they view their house as a refuge, oasis or retreat from the world. Modernism responds in kind - functionalism demands that if the house is to be a retreat, then privacy trumps any public role that a house might display. Our ambivalence or outright fear of the world at large directs us to make houses that turn their backs on the street, hiding and protecting the inhabitants. This is maybe not that different from medieval towns who faced the outside world with large defensive walls, not the light and airy facades of Enlightenment villas.

It is my practice to always study the context of a building with as much care and rigor as the program of the building. In my mind, the "function" of the neighborhood, its faces on the street, the proximity of other buildings, the rythym of the openings along the street, are all as much a part of the problem of the project as the location of a kitchen or the drama of a stair. For buildings in remote, rural settings the shape of the land and the context of trees and native plants along with the seasonal variations of light and views, make up the "neighborhood" of the building. However, in a more densely populated suburban or urban situation, the design of the building should reflect and respect some aspects of the scale, size, proportion and "openness" of the surrounding buildings. This does not mean that we typically mimic the style of the buildings around us, rather we look to some aspects of these buildings to see if there are some elements that might both reinforce the internal functions of the house as well as help relate the house to its context. That may mean we reflect the relative amount of window-to-wall proportion of the neighborhood or the base-shaft-capital vertical arrangement of a set of facades. Even when the new building is significantly larger than its older and more traditional neighbors, we make efforts to mitigate this scale contrast by various means - entering the building on a lower level, downplaying the colors and material, breaking down the scale of the new to reduce its visual scale.

So where do so many architects get off complaining that the public just doesn't get it and that anyone who doesn't like modernism is a dolt? When architects finally stop making bad corporate shit-box buildings and masterpieces to their own ego (and sometimes those of their clients) instead of recognizing the value of being a participating part of a larger whole then maybe modernism can regain its claims to humanism. Until then, if you want to design a masterpiece unhindered by neighbors and their mundane houses, feel free to buy a large chunk of land up in the mountains or out on the plains and let's go for it. But if you want to live in a neighborhood, then be a good neighbor.