Frank Lloyd Wright's Meyer May House, Grand Rapids, Michigan

This last summer I had the opportunity to be in Grand Rapids, Michigan, home of Steelcase furniture, and the magnificently restored Meyer May house. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, the house was designed and built just as Wright's marriage was falling apart and he was soon to depart to Europe to escape the scandal and notoriety.

This last summer I had the opportunity to be in Grand Rapids, Michigan, home of Steelcase furniture, and the magnificently restored Meyer May house. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, the house was designed and built just as Wright's marriage was falling apart and he was soon to depart to Europe to escape the scandal and notoriety.

Like the Robie House, designed in Chicago just a year or two earlier, this house sits on a residential corner lot and shares with as well Wright's signature hidden entryway and layered horizontal composition. Even though the Robie House is more dramatic, being more decidedly long and narrow, the Meyer May house actually does a better job of addressing the spatial situation of the corner lot. However, this does lead to a fairly complex interior with spaces driving in two directions, maybe anticipating the more pinwheeling designs of later houses.

You can see many of the typical Wright details here - the flush vertical joints and deeply scored horizontal joints of the masonry, the wide cantilevered, hovering roof planes, the delicate leaded windows.

And, like in some many of Wright's houses built during this phase of his career, a complex and devoted attention to some rather fussy details like these Living Room windows. One can't help but speculate that this heavy grille work on street-facing windows was as much defensive as decorative, a spill-over from Wright's domestic troubles, keeping the world at bay as much as providing light and views. I have often thought that his growing predilection for the increasingly hidden and obscured entries of houses of his from this period are also an echo of the growing demand for privacy and avoidance of the public gaze that eventually surfaces in Wright's full retreat from Oak Park and Chicago to rural Spring Green, Wisconsin.

In any case, the Meyer May house is not only an excellent and under-appreciated work of Wright's from this period, it is also one of the very best examples of a period restoration that feels complete and careful without feeling like a museum (even though it is of sorts). Steelcase purchased the home in 1985 and painstakingly restored the entire structure including sourcing many Wright-designed furniture and textile pieces to fill it. And best of all and a great testament to the new owners, the house is fully available for tours for FREE, no reservations needed. Thank you Steelcase for the great renovation and most importantly for allowing it to be viewed by anyone.

author-illustrator studio construction progress

We are making good progress on the construction of a new studio in Boulder, Colorado for a couple who are artists, illustrators and authors of children's books.

We are making good progress on the construction of a new studio in Boulder, Colorado for a couple who are artists, illustrators and authors of children's books.

The project greatly increases the size of their existing studio and adds a second-level loft space. The original studio was a dark, poorly-constructed structure and it was awkwardly attached to their 1880's Second Empire house. Our new work involves creating a new studio that looks primarily to the west to take advantage of the deep space of their richly landscaped property. The link to the old house is created by a small hall whose eastern face is pulled back from the older house's front porch to allow the old house to have a more complete expression. This little reveal between the old and new is a small example of the project's attempt to create a positive dialogue between the old and new. The studio's size and position required us to make a building that might "compete" with the older house. Rather than fight with that formal issue, we used this potential problem as the central narrative for the project.

More updates to come as the construction progresses.

Builder: Cottonwood Custom Builders

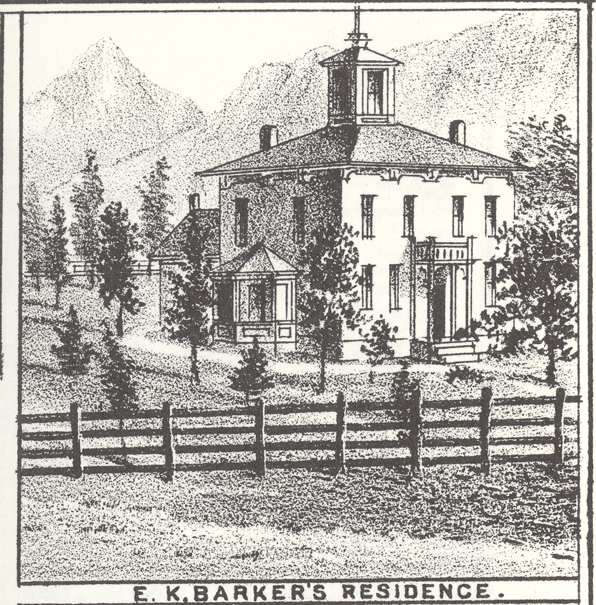

Hannah Barker house – preservation and perseverance

Yesterday Historic Boulder, our local non-profit preservation advocate organization, announced that it has purchased the long-unoccupied Hannah Barker house. Most folks here in Boulder know it better as that dilapidated, boarded up white elephant on Arapahoe west of 9th Street. Buying the house themselves certainly is a bold put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is move. And it is not the first time.

today

Historic Boulder largely got its start in an effort in the early 1970's to save the threatened Boulder Theatre. Rather than just picket the building and shout at some public hearings, they bought the building and secured it for a few years until a buyer could be found. They have done similar purchase-to-perserve efforts since including the Highland Lawn School which has become the Highland City Club building.

1880 drawing

Sitting on the Landmarks Board, I hear a lot of complaining about the entire preservation process. Maybe more than most places, in the West there is a strong owner's rights ethic that often runs smack into perservation efforts which attempts to protect our cultural heritage by primarily regulatory means. The recent success of Historic Boulder purchasing the Barker house mutes that conflict and lends immense credibility to the organization and the act of preservation in general. And in the end, Historic Boulder will take the risk and the community will gain the benefit of a truly architecturally and historically significant building saved.

One of the most interesting aspects of this project will be Historic Boulder's intention to use the renovation of the house as a model for demonstrating that preservation, old houses and sustainability concerns can all work seamlessly together. In Boulder we have a wealth of talented and experienced architects, builders, energy consultants and building science professionals that can be brought to bear on this project.

The building is currently a much-abused shell, but even in that state it has a tremendous amount of embodied energy that needs to be accounted for. Embodied energy is the all the energy inputs that the existing building represents - the energy required to lay the masonry, frame the house, and it also includes the trapped energy that was used in the creation of all those bricks and all that lumber, including its transportation.

Most energy conservation ordinances and programs do not give sufficient credit for embodied energy and rely more heavily on building systems and performance to meet sustainability goals. Embodied energy is difficult to calculate, but only by carefully stepping through this process can we have a quantitative marker that proves "the greenest building is the one already there."

circa 1885

Hopefully a careful and exhaustively documented renovation process can convince the City of Boulder and other municipalities that they must included embodied energy as an integral part of their sustainability regulations and give it it's proper credit. At that point, perservation and sustainability can be partners, not often contentious constituents.

Congratulations to Historic Boulder and all its volunteer members who made this possible, as well as the City of Boulder preservation and planning staff that aided in this much-needed process.

(All image from Historic Boulder and/or The Boulder Public Library, Carnegie Branch for Local History)

Altona Grange hall

Just north of Boulder, Colorado is the Altona Grange Hall. It is one of the original 492 granges in Colorado, established in 1891. These buildings were built as part of the Grange movement of farmer solidarity known as the Patrons of Husbandry. They advocated for modern farming techniques, water rights protections, bank farm loan policies and railroad price fixing. The buildings become the social center, the "culture" of agriculture, of often very isolated farming communities.

These are buildings built without architects, usually by the farmers themselves. Unlike Europe where so many farmers live in town and migrate daily out to their fields, the homestead movement in the United States occupied the land in a much more dispersed fashion. Farmers often lived great distances to cities or town and from each other. These buildings are some of the richest examples of truly vernacular building in the West.

The Altona Grange has a long and rich history and is still a thriving enterprise. http://altonagrange.pbworks.com/

I find the building fascinating in its lack of consistency to roof pitches, materials usage, etc. As you can see, the siding and roofing changes for different locations, the various additions wrapping around the original building based on use and necessity, not aesthetics. But what ends up is a really dynamic building.

This is architecture put together by the people who use it and have to maintain it collectively. It is not graceful or delicate, but it has a solid presence that comes from occupation and some very clear relationships. The main building is clearly dominant and the additions and sidecars are secondary. You can tell from looking at the building that the main hall is the center of the community, the other forms are there to support that main function. This is a simple, albeit not elegant, description of "spaces served and spaces in service" that Louis Kahn delineated in most of his better works and gives a building a clear sense of both its genesis and use.

This modest building serves as a good lesson to architects designing buildings that stand isolated out on the plains. A simple, strong form needs to be strongly articulated to sit in the massive panaroma of the landscape and the small additions lend human scale and occupation. A beautifully simple building more satisfying that so many current architectural flights of fancy.

Richard Nickel – photographer, preservationist, hero

"Great architecture has only two natural enemies: water and stupid men." - Richard Nickel

The archive of photographer Richard Nickel was recently donated to the Art Institute of Chicago. Nickel is a hero in the Chicago preservation and architecture communities for his early and dedicated work to preserve and document so much of Chicago's early architectural history. Working throughout the 1950's and into early 1970's, Nickel tirelessly recorded much of the work of Adler and Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, Holabird and Roche, Frank Lloyd Wright and others. These were the ugly, dark days for urbanism and architecture in the US, as hundreds of magnificent buildings were demolished by private developers and public institutions to make way for "progress" and urban renewal. What was lost was priceless buildings, glorious creations of great architecture and great neighborhoods.

Nickel not only took countless photos of endangered buildings, but he was also an ardent campaigner against the kind of wanton destruction that some Chicagoans were attempting. The demolition of Louis Sullivan's work was Nickel's prime target and his efforts included not only taking photos but saving actual pieces of soon-to-be-demolished buildings. The interior of the Chicago Stock Exchange building is a part of the Art Institute, on permanent display, due his work and that of other zealots he recruited. Louis Sullivan is now known as one of the greatest of all American architects and much of his body of work exists solely in Nickel's archive.

Nickel's story ended tragically and in some mystery. His body was found inside the demolition site of the Chicago Stock Exchange building, buried under a collapsed stair. Under great risk, he often entered building sites where demolition was already underway, and his photos are often the only documentary evidence that exists of so many buildings. In the case of the Stock Exchange, he returned many times after the official salvage operation was complete to retrieve and document.

His archive, some 15,000 photographs, prints and negatives, has been held by The Richard Nickel Committee and available for viewing only by professionals and academics. Hopefully now that it is housed at the Art Institute, some of this man's heroic and beautiful images can be viewed more easily by the citizens of Chicago, who have benefited so powerfully from his heroic efforts.

For more info on Nickel, I recommend They All Fall Down by Richard Cahan, on Nickel, his preservation efforts and those of Chicago architect John Vinci.