Maybe it is just a coincidence, but I are finding that I am working on a number of projects that deploy universal access principles as a major part of the design process. If you are not familiar with this term, universal access is an outgrowth of the barrier-free design guidelines that we were all using for public buildings just a few years ago. The idea of universal access however encompasses not just guidelines for wheelchair users, but recognizes that curb cuts aren't just necessary for them, but aide folks with strollers and kids with skateboards. It is an acknowledgement that we all age and designing to accommodate the needs of the many probably benefits us all at some time as individuals.

My father has serious mobility issues and my sister and I have spent an increasing amount of time over the last few years trying to reconfigure and adapt his typical suburban house to his needs. After a broken hip, we quickly realized that the door to the master bath, a door he has used for over 25 years, is now 2" too narrow to allow a walker to slide through. The shower in that same bath is too narrow to allow a seat to easily fit and the handle of the shower door is too easily confused with a grab bar. Same with all the towel bars. The laundry downstairs has been abandoned as has the back entrance, which although it is almost at grade level, has an absurdly slippery deck that no amount of friction tape seems to ameliorate.

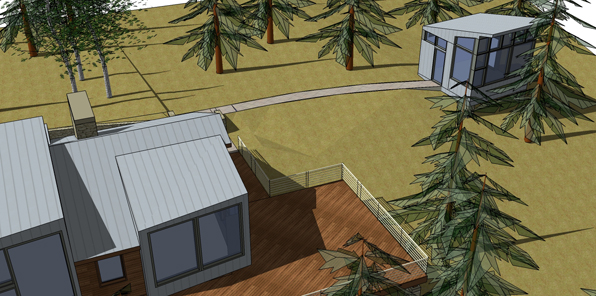

These are good lessons for an architect. We are all adept at designing to codes and the guidelines of the Americans With Disabilities Act. But the actual, everyday experience of seeing my father trying to navigate the kitchen has taught me so much more. And rarely have architects applied these universal design principles to single-family houses for aging-in-place prospects. I am currently working on a project that is a father-in-law suite that subtly incorporates universal design principles. It looks clean and simple and elegant and is also going to be a great asset to his daily living. At the same time, we are engaged in the early stages of two projects that directly confront the needs and desires of wheelchairs users. Seeing the house from that point of view, both actual and metaphorical, is a fascinating challenge and it reframes the poetic possibilities of every part of the house that we so easily overlook.

A pair of design presentation boards we did for an urban universal design competition for a neighborhood in Chicago from 2005: