A number of months ago a wrote a series of posts about Colorado's vernacular architecture. I attempted to categorize the vernacular buildings by the dominant material - log, stone or frame. Sadly missing from that collection was the base building material used by the Spanish colonial settlers in southern Colorado - adobe.

As most folks know, adobe is a sun-dried, hand-formed brick made of local sand, clay, water and some binding fiber like straw. Adobe construction has been used in many cultures and over thousands of years and is particularly well-suited to hot, dry climates because of its dense thermal mass.

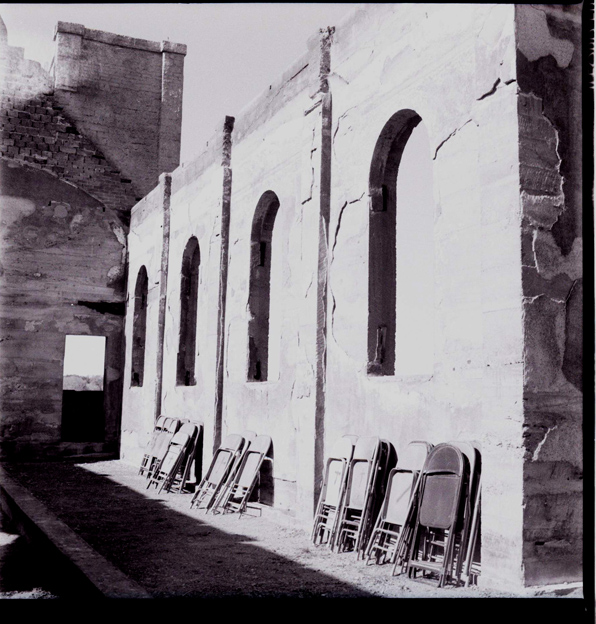

In southern Colorado, along the east and west sides of the San Luis Valley, there are numerous examples of very old adobe structures, many of which have been slowly replaced with more conventional concrete block construction. In fact, when white-washed, it is very difficult to tell at a glance if the underlying structure is adobe or concrete unit masonry. The adobe construction is generally limited to single story rectangular buildings that could be simply spanned by vigas or lumber framed roofs.

When left unadorned, the adobe bricks weather, their edges flaking off, creating a soft, pillowing profile that adds to their impression of mass and weight. As a testament to their enduring nature, you can find many structures long devoid of their wood roofs and doors, with the adobe still standing. The precious little dressed lumber that was used is placed to make uniform and contained window and door frames, further accentuating the adobe's soft forms.

I don't know where the line is struck in southern Colorado, but some place slightly north of Alamosa I would guess the use of adobe was found too incompatible with the increased snow and rain fall. These adobe structures are certainly part of the Colorado vernacular environment and like the simple log and stone structures of the mountains, they are equally geographically limited.