At the end of another year and another oh-so-typical list of the year's best and worst. Not Best-Dressed, as I am not even vaguely qualified, not even Worst-Dressed, which I might even have a shot at. No, it is the year-end,

ARCHITECTURAL TRENDS WE LOVE TO HATE (and some good stuff as well)

first, let's throw out our usual qualifier: as I am not exactly in one of the world's architectural hot-spots, my notion of what is over-exposed and trendy comes from the webinet and trade magazines. So this is not a list so much of the good and bad in the year's architecture as it is a gleaning of the architectural press and their obsessions, good and bad over the last 12 months.

The Good

This year definitely has seen an increase in the number of architect blogs - not the strictly professional type, but more personal. Replacing, or at least supplementing the design-candy pages of aggregator sites like materialicious, or the vaguely academic tone and personal remoteness ofBLDGBLOG, these sites tend to discuss the nature of being an architect and have been heavily weighted toward the concerns of a profession in an economic and moral decline. I find these refreshing and a recognition that though we are architects, we are also human beings, and our thoughts, desires and concerns come to bear on our projects, not just our fancy educations and "natural born talent".

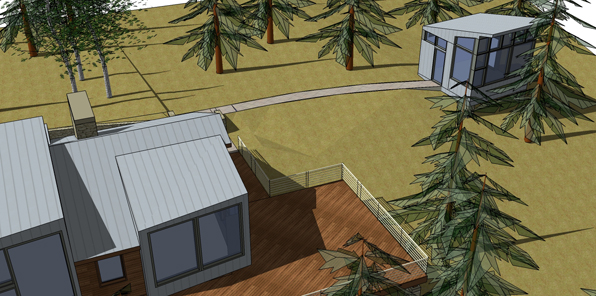

The proliferation of the pavilion as the focus of architectural fascination and experimentation has been all too apparent this year. Many of these are executed by unknown, young architects as a way of getting exposure. Young architects need every foothold they can secure in a profession where usually only the well-heeled designers get the best commissions and usually reproduce previous work.

The Bad

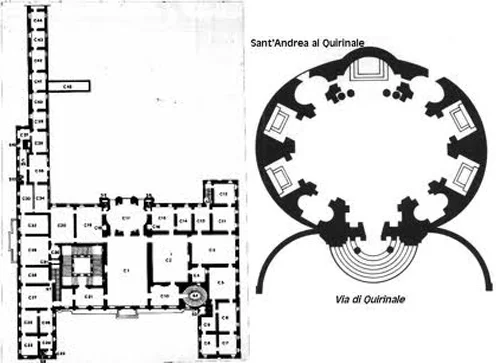

The most disturbing trend of the year, and I think a clear result of too many architects with too much time on their hands, has been the return of the megalopolis project designed by architects. In the late 1950's and early 1960's these ginormous projects were either horribly designed and generally racist urban renewal projects or architectural fantasies envisioning a utopic post-WWII world. They at least had some charm in their naivete' as long as they weren't actually built. When the were built, or partially so like Paul Rudolph's Government Center in Boston, they more often than not displaced vibrant communities with dreadful environments. It has always been my belief that one of the most gratifying and positive outcomes of the critique of Modernism after this era was the realization that the will-to-power that these projects embody was the last death cry of a kind of technocratic fascism. Great places are made up of the small accretions of many buildings over many years, not planned by a few elitist experts and plopped down on the unsuspecting, and unsolicited, public. Lesson learned.

Or may not. It seems like any time an architect has too big a site and budget or too much time, they come up with these things. In 2009 there were giant projects that resembled some eco-architecture mountain or forest. Now, in the guise of planning sustainable communities and re-thinking our relationship to the earth, we get these ridiculous and ultimately disastrous monster projects. You may say that there is no threat that these will actually get built, but their proliferation makes it all the more acceptable to think in these terms and it is only a matter of time before some politician or corporation starts to execute such a scheme. After all, the architectural press has given breathless praise to these megalopoli, so why not build one. It seems Sir Norman and Apple may have already started.

One of the trends which has been increasing in 2010 is the frankly awful names that have sprung up for architecture firms. This was a subject of an earlier post, so I won't dwell on it here, but I will be glad when the recession is over and architect's can afford some quality graphic design and brand consultants to put an end to this.

With the good comes the bad, and I think the pavilion as the ground for architectural expression and experimentation has a dark side as well. As I mentioned above, pavilions can be a great way for clients, be they cities or institutions, to try out the talent of young architects at a moderate cost and risk. However, just as many have been by well-established star-architects, like Zaha Hadid, and I think represent an ongoing trend of architectural consumerism. Call it a mini-Bilbao effect, but it seems like every city wants a star-architect building, and the recession has put an end to extraganzas like the Denver Art Museum by Libeskind and given us instead more affordable, and frankly disposable, star-architect pavilions. If it turns out that the city leaders don't like it, trash it. If it leaks, no problem, it's just a pavilion, it wasn't really meant to last. I'm not knocking the architects who design these - they are given a project like a pavilion and they work at that. But we should not loose perspective that a fully functioning building places significantly more demands on its architecture than any pavilion. Pavilions are great architectural appetizers, but a meal they do not make.

And, not to step up on the same old soap box once again, but the trade rags have continued in their appraisal of architecture as a merely visual phenomena to the exclusion of actually visiting and experiencing a building as something other than an eyeball. To some extent the exclusively visual analysis has begun to be supplemented by the usual slue of green stats - energy consumption, energy production, etc. However, for me this is still not even scratching the surface of the totality of what a building is, how it effects us, and what it may mean for us as individuals and a culture. How about talking to people who use the building and what it's like to be there? Maybe too much work for architectural "journalists"?

The Ugly

The economy. Even though the AIA Billing Index may have begun to tilt up a bit in the last few months, it is still ugly out there. I know too many unemployed architects, too many architects working for less, working more and sweating it every day. Now there is no reason why architects should be immune to the ravages of the economy, but I am very concerned about how hard this sector of the economy has been hit and what the future of the profession might hold. There probably were too many architects out there. On the other hand, there is no question that there are too many badly designed and poorly built buildings filling our cities, towns and countryside. For a better built environment we need more and better architects, not fewer and more scared.

The dire economy has lead many architects to question the most basic underlying foundations of the profession:

What is architecture? Why is architecture so undervalued? Do people want architecture? Are all architect's educations fundamentally alienated from both the everyday practice of architecture and the needs and desires of people?

I don't know the answer to any of these questions and it may be a good outcome of the bad financial times that we are asking these questions. But frankly I fear some of the answers, none more so than the increasing speed at which people will feel the need and desire to throw architecture under the bus when even the whiff of economic hard times flutters by.

On a cheerier note, the new year is upon us and with that has come a new form and format for this blog. We combined the blog with M. Gerwing Architect's website and another blog to hopefully make a more cogent place for understanding architecture and our approach to it. And it looks way cooler too.