a parti diagram is an idea sketch, an initial response to a site, a client’s program or some other conditions that begin to determine the order for designing a project. They don’t really represent what the project will look like in plan or elevation, but are a road map of the ideas of the project. Ideas of ‘threshold’, ‘tension v. repose’, ‘horizon and center’, or ‘territory and enclosure’ all can be simply diagrammed in the parti as an initial response to the problem posed by a new project.

author-illustrator studio construction progress

We are making good progress on the construction of a new studio in Boulder, Colorado for a couple who are artists, illustrators and authors of children's books.

We are making good progress on the construction of a new studio in Boulder, Colorado for a couple who are artists, illustrators and authors of children's books.

The project greatly increases the size of their existing studio and adds a second-level loft space. The original studio was a dark, poorly-constructed structure and it was awkwardly attached to their 1880's Second Empire house. Our new work involves creating a new studio that looks primarily to the west to take advantage of the deep space of their richly landscaped property. The link to the old house is created by a small hall whose eastern face is pulled back from the older house's front porch to allow the old house to have a more complete expression. This little reveal between the old and new is a small example of the project's attempt to create a positive dialogue between the old and new. The studio's size and position required us to make a building that might "compete" with the older house. Rather than fight with that formal issue, we used this potential problem as the central narrative for the project.

More updates to come as the construction progresses.

Builder: Cottonwood Custom Builders

Mine the Gap - Late Entry

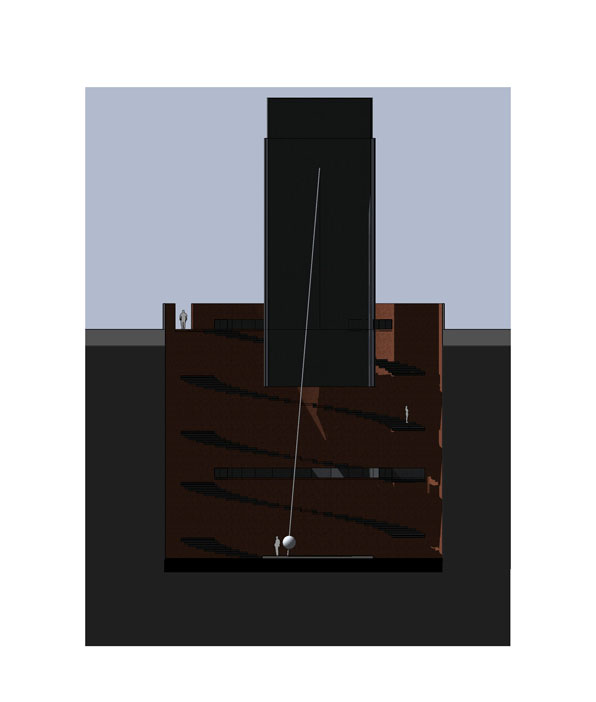

The Chicago Architectural Club ran a competition last year to elicit ideas about what to do with the ill-fated Chicago Spire project. Our entry was never really considered for submission, but has been worked on and off since.

The Chicago Architectural Club ran a competition last year to elicit ideas about what to do with the ill-fated Chicago Spire project. Our entry was never really considered for submission, but has been worked on and off since.

Designed by Santiago Calatrava, the Spire was to be the self-described "most significant residential development in the world". (go to the website to view the over-the-top video and especially the musical track). It ran afoul of bad economic times and the Anglo Irish bank put a halt to the whole thing after only the gigantic 70' deep, 70' diameter foundation had been excavated alongside Lake Michigan on the eastern most edge of the city. (in an amazingly myopic moment, Calatrava described his twisting design as an imaginary smoke signal coming from a campfire near the Chicago River lit by indigenous Native Americans. An incredibly insulting and tone-deaf explanation that negates a couple hundred years of excellent Chicago architecture and is a lame attempt to justify a twisting, spiraling design that Calatrava has experimented with all over the globe. As if genocide wasn't bad enough, lay off the native Americans already, don't implicate them in this placeless monstrosity.)

I can't help but see the hole as a grave dug by the recession to bury developer's hubris. In light of that, our competition entry envisioned a slightly dystopic future for the site as an enormous time-keeper, with a Foucault pendulum slowly swinging away marking the passage of days until the whole reinforced foundation inevitably floods from below from seeping Lake Michigan.

Not a pretty building to cap an ugly incident in the city's history of over-reaching development. Maybe we could have just filled up the hole with the demolished remains of the Cabrini Green housing project.

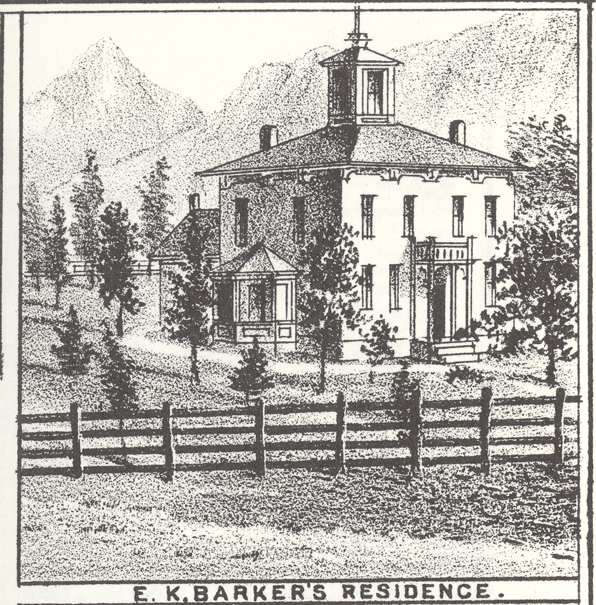

Hannah Barker house – preservation and perseverance

Yesterday Historic Boulder, our local non-profit preservation advocate organization, announced that it has purchased the long-unoccupied Hannah Barker house. Most folks here in Boulder know it better as that dilapidated, boarded up white elephant on Arapahoe west of 9th Street. Buying the house themselves certainly is a bold put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is move. And it is not the first time.

today

Historic Boulder largely got its start in an effort in the early 1970's to save the threatened Boulder Theatre. Rather than just picket the building and shout at some public hearings, they bought the building and secured it for a few years until a buyer could be found. They have done similar purchase-to-perserve efforts since including the Highland Lawn School which has become the Highland City Club building.

1880 drawing

Sitting on the Landmarks Board, I hear a lot of complaining about the entire preservation process. Maybe more than most places, in the West there is a strong owner's rights ethic that often runs smack into perservation efforts which attempts to protect our cultural heritage by primarily regulatory means. The recent success of Historic Boulder purchasing the Barker house mutes that conflict and lends immense credibility to the organization and the act of preservation in general. And in the end, Historic Boulder will take the risk and the community will gain the benefit of a truly architecturally and historically significant building saved.

One of the most interesting aspects of this project will be Historic Boulder's intention to use the renovation of the house as a model for demonstrating that preservation, old houses and sustainability concerns can all work seamlessly together. In Boulder we have a wealth of talented and experienced architects, builders, energy consultants and building science professionals that can be brought to bear on this project.

The building is currently a much-abused shell, but even in that state it has a tremendous amount of embodied energy that needs to be accounted for. Embodied energy is the all the energy inputs that the existing building represents - the energy required to lay the masonry, frame the house, and it also includes the trapped energy that was used in the creation of all those bricks and all that lumber, including its transportation.

Most energy conservation ordinances and programs do not give sufficient credit for embodied energy and rely more heavily on building systems and performance to meet sustainability goals. Embodied energy is difficult to calculate, but only by carefully stepping through this process can we have a quantitative marker that proves "the greenest building is the one already there."

circa 1885

Hopefully a careful and exhaustively documented renovation process can convince the City of Boulder and other municipalities that they must included embodied energy as an integral part of their sustainability regulations and give it it's proper credit. At that point, perservation and sustainability can be partners, not often contentious constituents.

Congratulations to Historic Boulder and all its volunteer members who made this possible, as well as the City of Boulder preservation and planning staff that aided in this much-needed process.

(All image from Historic Boulder and/or The Boulder Public Library, Carnegie Branch for Local History)

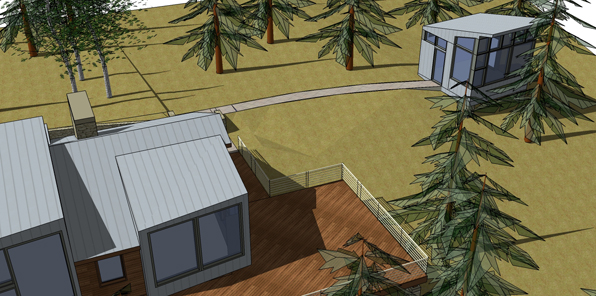

live – work

In the past few years I have had the opportunity to work on a number of projects that fully incorporated a live-work dynamic as a fundamental part of the house. More than simply a home office, a fully-utilized live-work program creates a kind of tension of use and privacy that most homes in the last one hundred years or so have not encountered.

Most of the projects like this that we have worked on included a single large office or studio. And the variety of work has differed greatly but all with one similar aspect - the ability, via computers and the internet, to communicate visually, verbally and to a great degree of satisfaction - with a remote office or clients. Rarely do these home offices or studios include a separate entry for clients or employees because the work in question does not require it. More often, my clients work at home and take the drive to the airport on a regular and frequent schedule to meet with their clients and co-workers.

So what is the nature then of these home offices? They are not the 19th century gentlemen's study, a place of retreat and contemplation. They are wired and connected not just functionally, but also culturally, to distant places and all to the landscape that is the internet. More trips are taken to Google than the local coffee shop. What is the nature of "privacy" in a space in your house that is open to so much of the world with the only "threshold" of a keyboard and/of mouse?

In looking at these projects and working on some current live-work projects, what occurs to me is that in each project we have tried to ritualize the passage in the house from the working space back and forth to the rest of the house. In the images above, for a condo renovation, the office was on a half-level between the main level living spaces and the upper floor master bedroom. We focused effort on the stair and tried to create a unique space, with light streaming down from skylights, to set this passage off from the more conventionally proportioned rooms. In addition, we installed a series of semi-transparent resin panels on both sides of the stair to modulate the sound and views from the office to the rest of the house. The public-private dialogue that takes place across this stair makes a kind of liminal threshold that makes the mental shift to and from "working".

In the project above, we designed a simple writer's shack as an additional outbuilding to a cabin renovation in rural Colorado. The shifted geometry of the writer's shack reverberates back through the cabin as series of new dormers, inserting the "working" within the "living". And again, the path between the buildings, a simple path through the woods, is designed as a careful separation - just far apart for a sense of separation, but not too isolating. That ritual of walking between the two, with a cup of coffee in hand, boots on but not laced up, the pupils adjusting to and from the bright, Colorado high-alpine sunshine, makes each building a distinct place, the occupation intentional.

The image above is a home office we designed, very warm and internalized, that looks out to a mountain vista. This is a built analogue of the relationship of the home-based office, secure and private, looking out via the internet, to the rest of the electronic world.

I'm not sure how the issues of the private office and the public connectivity play out for a project - that relationship varies with each client and each space. I do know however that just putting a desk in an unused bedroom does not really address the live-work issue and forsakes a potentially rich landscape of ideas and use that is architecture.

the new small house – or maybe not quite

There is a ton of press on the new small house phenomenom. As a response to the excesses of consumption and the economic turmoil of the last few years, many architects, builders and inventors have created amazingly livable micro-houses.

There is a ton of press on the new small house phenomenom. As a response to the excesses of consumption and the economic turmoil of the last few years, many architects, builders and inventors have created amazingly livable micro-houses.

I was listening to an interview with one of these tiny house makers and he was mentioning that with technology, we can compress hundreds, thousands of albums and CDs into a single Ipod. And the same with books - eliminating them saves hundreds of square feet.

This sounded absurd to me at first until I took a more careful look around our house.

For some, the compression of many hundreds of books into a single, tiny disc is a revelation. However, I must admit that my books mean a lot more to me than the words inside them. I have lived in a few cities, moved many times. But the constant of books has given great solace to that kind of displacement. Looking at one's various bookshelves is like looking at a kind of biography of self.

If you get the opportunity, I would strongly recommend Walter Benjamin's essay Unpacking My Library in his collection entitled Illuminations.

So, while I would encourage everyone considering making a new house to reduce their assumptions of the size "required", I am too guilty of a kind of hoarding fetish when it comes to books. A micro-house may be the goal, but our impediments of self require considerably more than focusing a microscope on need and function and making that the totality of a house. That difference, between our needs and our wants, makes the ground for making architecture.